If it feels like brands aren’t talking about sustainability as often as they were a couple of years ago, that’s because they aren’t.

Though climate change is increasingly important to consumers — especially among younger generations, who prefer to support brands that take a stance and align with their values — the worry of being called out for greenwashing has marketers rethinking how they publicize data and information around sustainability initiatives.

Over half (58%) of companies recently indicated they are cutting back on sustainability-related communications, according to carbon project developer and climate consultancy South Pole, which in January released its annual Net Zero report based on a survey of 1,400 companies. The data showed that, for the first time, greenhushing is happening in every major industry sector.

The reticence comes as brands have been increasingly called out for greenwashing when their marketing doesn’t align with their actual environmental efforts. Instances of greenwashing saw a 35% year-over-year increase, according to a 2023 report from environmental, social and governance (ESG) data science researcher RepRisk.

“The crackdown on greenwashing really makes a lot of companies think twice before they say something,” said Wren Montgomery, associate professor of sustainability at Ivey Business School and co-founder of the Greenwash Action Lab, an anti-greenwashing researcher. “And it may be that they're actually doing things internally and trying to change, but they're just being a little bit more careful about the claims they're making and not overclaiming about what they're doing.”

When companies that have emphasized a strong ESG stance face backlash, this can cause damage to a brand that isn’t always easy to bounce back from. Take Volkswagen, which is a particularly notorious instance of a brand being called out for greenwashing after it was found to have falsified emissions data to align with a greener marketing message in 2015, something the brand and company did not recover from quickly. The automaker joins a list that includes the likes of McDonald's, Nespresso, Starbucks, Coca-Cola and more that have been lambasted in a similar way.

From greenwashing to greenhushing

After several years of sustainability being a focal point for many marketers, it’s noticeable that a significant portion are now holding back from sharing their sustainability-related initiatives. However, it isn’t an entirely new trend.

Some reporting traces the first mentions of greenhushing to 2017. And, in fact, South Pole reported on the trend accelerating in its 2022 annual report, where it found that despite having emissions reduction targets, one in four companies surveyed didn’t plan to share information around those plans.

But the trend accelerated after more litigation was borne out of false advertising class-actions lawsuits (aka accusations of greenwashing). For instance, fast-fashion retailer H&M and footwear and apparel brand Allbirds, among others, were sued for positioning their products and manufacturing processes as eco-friendly. And though the cases were dismissed, the brands had to deal with the subsequent flack they received from consumers and the media.

“In my view, greenwashing typically occurs due to a lack of education rather than deliberate deception,” said Mastercard Chief Marketing and Communications Officer Raja Rajamannar. “It’s essential that marketers fully understand sustainability terminology, understand the impact of their actions and communicate transparently with consumers.”

There are also intensifying efforts across the U.S. and Europe to require brands to report emissions data, something that’s currently voluntary. This includes the Federal Trade Commission, which created its Green Guides in 1992 and has been updating it as perception and cultural attitudes to climate change have changed. The latest edition is expected to arrive later this year.

With terms like “green,” “sustainable” and “eco-friendly,” for instance, the FTC is pushing for more specific language so consumers can make informed decisions based on their priorities and what they’re looking for. The guidance also requires that brands outline targets and timelines for any assertions about reaching net-zero emissions.

“Companies are aware that regulations are changing, and in a regulatorily uncertain environment, it is easiest or safest to do nothing and wait and see how the dust settles,” said Austin Whitman, CEO and co-founder of nonprofit The Change Climate Project.

Less information means less accountability

With so many risks involved, it makes sense that brands are more inclined to pull back on publicizing communications to avoid potential litigation or PR blowback.

"What the pullback does is it kind of puts [brands] back in this space of just collecting data and not actually trying to report on plans to improve [company] performance," Whitman said.

One of the biggest downsides to greenhushing is the loss of momentum. Though sustainability initiatives won’t completely disappear, the publicity keeps it top of mind for consumers and other marketers. Without sharing research and progress — and even missteps — publicly, marketers won’t have the ability to learn from one another and keep up competition to develop different approaches.

“Collaboration and the exchange of best practices are essential for advancing our shared goal of environmental stewardship,” said Rajamannar.

Though this wouldn’t be the first time the industry has found itself in a period of cutting back on green conversations, Whitman noted. The “last cycle” of cutting carbon emissions came 15 or so years ago, but lost momentum — and with it, a decade of experimentation and development. With where climate change stands now, though, “we can’t afford to lose momentum,” he said.

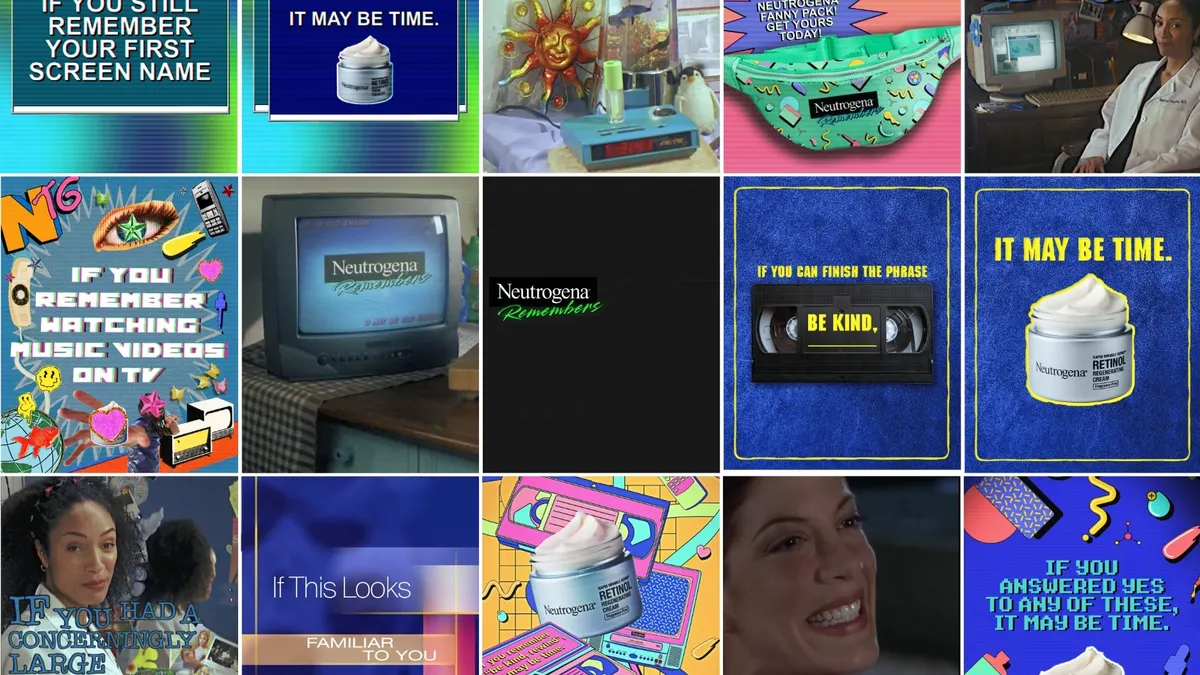

In fact, marketing around sustainability has an “inherent cyclicality” to it, he added. The brands that started exploring green initiatives, say, five years ago experienced a grace period in those first few years where they could experiment. Then came internal scrutiny over whether the initiative made business sense and delivered ROI for a brand, which is the phase the industry is in currently.

“As a result of that, [brands are] talking less about [their sustainability initiatives], and they're getting rewarded for it,” Whitman said. “Because by talking less, now they're exposed to less scrutiny and, frankly, less risk.”

Transparency fuels accountability

Greenhushing might not be all bad, according to Greenwash Action Lab’s Montgomery. Though brands are holding back from publicly sharing their sustainability goals and plans, within the industry there may be more transparency.

Due to stricter regulations that are emerging, like the Green Guides, and other pushback to greenwashing, brands are more reluctant to refer to their product as “eco-friendly” or “eco-conscious” if they don’t have the proof to back it up. But that doesn’t mean they’re pausing their work toward reducing emissions and creating greener products.

Which is evident in South Pole’s research and reporting from nonprofit climate advocacy news organization Grist. Of the publicly listed companies surveyed, 89% have a net-zero target and over three-quarters of the climate-conscious brands are increasing budgets to help reach those goals.

“Everybody’s trying to be responsible and to do things the right way,” said John Osborn, U.S. director at trade group Ad Net Zero. "But it can be hard to know the best way to proceed, which is why transparency about what is and isn’t working becomes essential."

Without transparency, each brand can end up working in a vacuum toward similar goals, without knowing whether it’s a step in the right direction or not.

In general, the brands and executives that Greenwash Action Lab’s Montgomery has spoken to want to take the right steps but are worried they’ll misstep.

“That’s where I really think some of the new regulations coming in will help,” she said. “It's more of a level playing field. People aren't just guessing.”